| North

High School Wall of Honor Donald H. MacRae Class of 1914 Killed in Action; March 5, 1918 |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

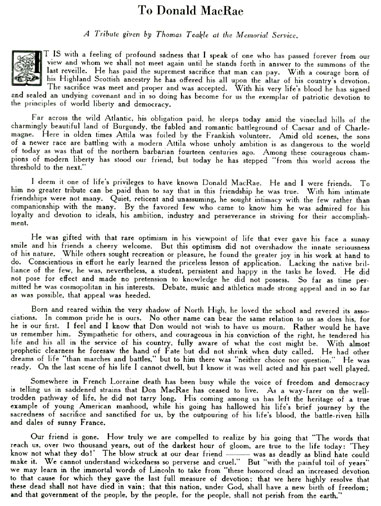

| Research done by Rick Nehrling, Class of 1963 and Claradell Shedd, Class of 1953. Eulogy given for Corporal Donald H. MacRae by a friend, Thomas Tenkle. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Donald was

born in April 1895 to Murdo and Metta MacRae. He was the oldest of four

children. The other MacRae children were Harold, Elenore, and Alexander. In 1900 the MacRae's were living in Des Moines where Murdo was working as a merchant selling butter and eggs. At this time Donald was 5 and his brother Harold was 1. By 1910 the other children - Elenore and Alexander were born and the MacRae's were living on Park Avenue. Murdo was still a merchant selling butter and eggs and Metta was a music teacher specializing in voice. Donald graduated from North in 1914. He enlisted in the US Army in May 1917 and was stationed at the Des Moines Fairgrounds until August 7, 1917 when he was assigned to the 168th Infantry Regiment, 42nd Infantry Division. The 168th Infantry Regiment sailed for France in November 1917. Donald, a corporal, was killed in action fighting with Company A, 59th Infantry, 168 Infantry Regiment, 42nd Infantry Division on March 5, 1918. He is buried in Plot D, Row 23, Grave 23 in the Meuse-Argonne American Cemetery, Romagne, France. MacRae Park in Des Moines is named after Donald MacRae. During World War I the United States lost more than 100,000 troops. Most of the deceased troops were buried in makeshift graves overseas. The War Department gave the next-of-kin a choice: bring the body back home for burial in the United States or let it remain for permanent burial in one of eight cemeteries in France, Belgium and England. Most chose burial in the United States, with a chance to hold a hometown funeral. However, approximately 33,000 families chose to let their sons and husbands remain buried in Europe. The MacRae's chose to have Donald's body remain in Europe and be buried in an American cemetery. During the 1920s the Gold Star Mothers' Association lobbied for a federally sponsored pilgrimage to Europe for mothers with sons buried overseas. Although a number of the women who belonged to the organization had visited their son's graves, they realized that many of the gold star mothers who had son's buried overseas could not afford the trip to Europe. Getting the US Government to fund and conduct pilgrimages was a 10-year effort. In their testimony before Congress, the Gold Star Mothers placed great emphasis on the bond between a mother and son. Congress boasted many strong advocates for government-funded pilgrimages. New U.S. Representative and future New York City Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia introduced the first pilgrimage bill in 1919. Ten years later in 1929 Congress enacted legislation that authorized the secretary of war to arrange for pilgrimages to the European cemeteries "by mothers and widows of members of military and naval forces of the United States who died in the service at any time between April 5, 1917, and July 1, 1921, and whose remains are now interred in such cemeteries." Congress later extended eligibility for pilgrimages to mothers and widows of men who died and were buried at sea or who died at sea or overseas and whose places of burial were unknown. The pilgrimages were funded, organized and conducted by the Federal Government. The War Department contacted every mother and widow that had a son or husband buried in an American Cemetery in France, Belgium or England and asked them if they desired to go on a pilgrimage and visit their love ones grave site. The Office of the Quartermaster General determined that 17,389 women were eligible for a pilgrimage. By October 31, 1933, when the project ended, 6,693 women had made a pilgrimage to Europe. Mrs. Metta MacRae responded that she desired to visit her son's grave at the Meuse-Argonne American Cemetery, Romagne, France. In 1930 the War Department arranged for Mrs MacRae to travel from Des Moines to New York City. From New York City she traveled with other Gold Star Mothers, who were also going to the Meuse-Argonne American cemetery, on a passenger liner to Cherbourg, France. From Cherbourg they traveled by train to Paris, France, where they remained for 3-4 days. From Paris they traveled toward the Meuse-Argonne Cemetery stopping on the way to visit some of the WWI battlefields - e.g. ChateauThierry, Belleau Wood. The town near the Meuse-Argonne American Cemetery - Romagne - was small and did not have restrooms or cafes that could efficiently serve Gold Star Mother groups. Prior to the visits the War Department had constructed a rest house near the cemetery. The rest house had tables, comfortable chairs, and restrooms as well as kitchen facilities. Each rest house had a shady porch for the hot weather and a large, open fireplace for the cooler days. On their initial visit to the cemetery the War Department had arranged for a simple reception. To make the visit as personal as possible, the War Department did not permit any ceremonies but focused on each Gold Star Mother's visit. The cemetery superintendent gave each Gold Star Mother a grave locator card and guided each woman to the grave. The cemetery also provided flowers or a wreath to put on the grave and took photographs of the grave. The women were allowed to remain at the cemetery for up to a week for a time of private mourning and reflection. After the cemetery visit the women traveled back to Paris and then by rail back to Cherbourg where they boarded a passenger liner and returned to New York City and then home. The trips averaged a little over a month. The pilgrimages were not without controversy. The War Department segregated black women from white women and forced the black women to travel on separate pilgrimages. In addition, a number of citizens protested what were perceived as "luxury" foreign trips |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Links: North

High: http://www.ndmhs.com/. Donald H. MacRae's 1914 class page: http://www.ndmhs.com/pages/yearclass1914.html. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Deceased: March 5, 1918 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Music: "Over There" | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Home

|

Back/allyears |

WWI |

WWII |

Korea |

Vietnam |

Afghanistan/Iraq |

Lyrics

|

Refs/Awards |

Contact ©2025-csheddgraphics All rights reserved. All images and content are © copyright of their respective copyright owners. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||